History of Religions in Liberia

Traditionally, all the people groups in Liberia were animists. The Vai was the first Muslim tribe to migrate to Liberia in the 16th century. The Mandingo tribe were also Muslims and came to this area from the western Sudan in the 17th century. [1] Christianity subsequently arrived in the 19th century, with the return of freed slaves from the Americas.

An Array of People Groups

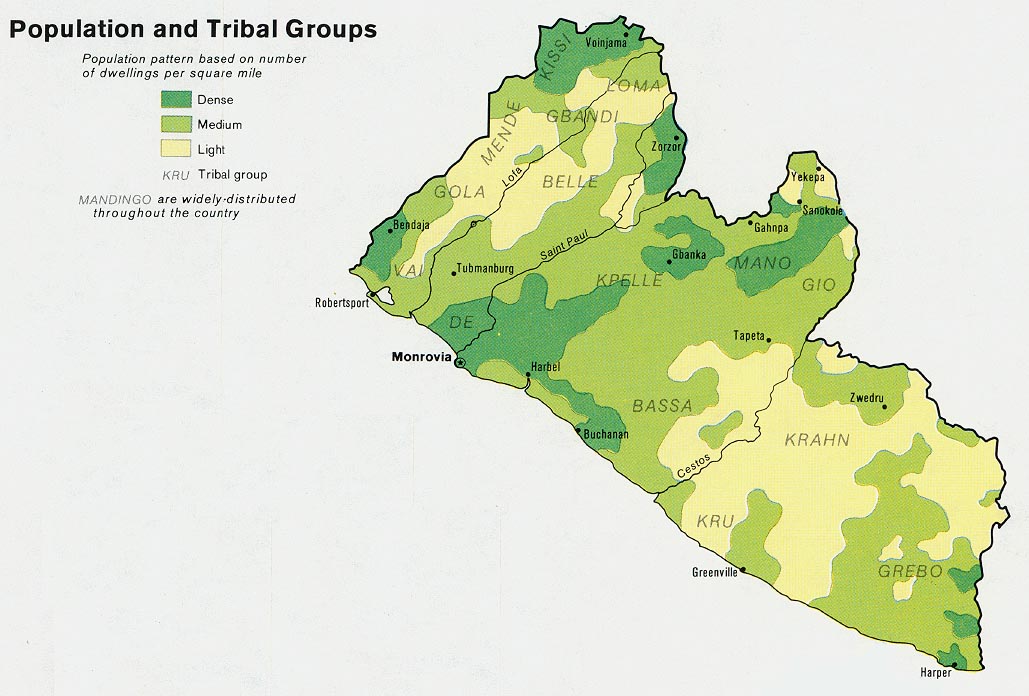

As in many parts of the world, political boundaries in Africa traverse a myriad of people groups, each with its own distinct culture and, often, language. Liberia has close to 40 people groups [2], but only 16 of them are officially recognized tribes. [3]

Source: http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/africa/liberia_pop_1973.jpg

Religions in Liberia

According to official statistics (the 2008 census):

- 85.5% of Liberians are Christians

- 12.2% of Liberians are Muslims

- 0.5% of Liberians adhere to ethnic religions [4]

However, Patrick Johnstone's 21st Century edition of Operation World paints a different picture: [5]

- 38.33% of Liberians are Christian, with an annual growth rate of +8.6%

- 13% are Muslims with an annual growth rate of +11.3%

- 48.37% practice ethnic religions with an annual growth rate of 7.8%

This disparity can be explained by the fact that many people and many groups incorporate elements of traditional animistic religions into their practice of Christianity or Islam.

The Joshua Project (www.joshuaproject.net) is a worldwide research initiative intended to bring clearer definition to the actual religious beliefs of people groups all around the world. Their determination in the case of Liberia's 16 official ethnic groups is as follows: [6]

5 are classified as predominantly Christian:

- Bassa (518,000) - 68% Christian, 16% Evangelical

- Kru (268,000) - 81% Christian, 17% Evangelical

- Belle (19,000) - 65% Christian, 7.5% Evangelical

- Grebo (365,000) - many groups predominantly Christian (approx. 10% Evangelical)

- Krahn (138,000) - Some Christian, some Ethnic religions

4 are classified as predominantly Muslim:

- Vai (130,000) - Muslims

- Gola (252,000) - Muslims

- Mandingo or Mandinka (97,000) - Muslims

- Dei (11,000) - Muslims

7 are classified as predominantly following Ethnic religions:

- Kpelle (983,000) - 38% Christian, 20% Evangelical

- Gio or Dan (186,000) - 25% Christian, 4% Evangelical

- Loma (241,000) - 15% Christian, 4% Evangelical

- Kissi (141,000) - 12% Christian, 5% Evangelical

- Gbandi (103,000) - 10% Christian

- Mano (367,000) - 8% Christian, 2% Evangelical

- Mende (29,000) - 10% Christian, 1% Evangelical

Highlights of ethnic religions in Liberia:

- The Kpelle religion focuses on ancestors, forest spirits, and especially on secret societies and the masked spirits that are represented in them. In the Kpelle belief system, there is a vague notion of "a High God who created the world and then retired. They believe in a variety of lesser spirits or genii, including ancestors, personal totems, water spirits, and spirits in magically powerful masks. Witchcraft and sorcery figure prominently in the belief system." [7]

- The Dan (or Gio) believe in a creator god, but not "that man can reach this god; thus, they do not worship him. Instead, a spiritual power called Du acts as mediator between the people and the supreme god. Du is said to really be the spirit located in each person. The Dan believe in reincarnation, in which the Du, or spirit, of a person can pass into another person or even an animal after death." [8] The Gio were one of the tribes most feared in colonial times because of their cannibalistic practices. [9]

- A major role in the religion of the Kissi people in ancestor worship or praying to deceased relatives. "The ancestral spirits act as mediators between them and the creator god," and the people represent these spirits with small stone statues. "They are worshiped and offered sacrifices by the village headmen." Witchcraft is commonplace, and people often wear charms as protection from evil spirits. Their lives are plagued with fear of the supernatural. Trances and hypnosis are often vehicles by which religious leaders communicate with spirits. Since the forest is believed to be a sacred place, this is usually where rituals are carried out. [10]

- According to the Mano, Wala is "the creator god who lives in heaven. However, the Mano have little idea of what heaven or life after death is really like. The Mano believe that small men or goblins live in the bush. The goblins are thought to be ghosts who have friendly relationships with people. However, the Mano believe that goblins may kill anyone who destroys their homes by clearing the land. Witchcraft also plays an important role in Mano beliefs. Witches often curse and sometimes kill their victims." [11] In colonial times, the Mano were feared because of their cannibalism. [12]

- The Mende believe in Ngewo, creator of the universe and all spirits. [13] They may not be very numerous in Liberia, but their influence is extremely widespread in their belief in the secret societies of the Poro (for men) and the Sande (for women).

Secret Societies

Native Christian workers from Liberia see secret societies as a deeply ingrained facet of the culture, and one that is not neutral in nature:

*According to the World Health Organization, 66% of Liberian women aged 15-49 have been subjected to female genital mutilation. [16]

Other dark practices also continue to plague Liberian society, including voodoo and ritual killing. [17] The secret Leopard society, now outlawed, was one of the most notorious for its involvement in such activities.

"Before the advent of Christianity in the 19th century, Liberia was a land of strongly entrenched and institutionalized secret societies involving almost every people group. While the culture and tradition of the Liberian people were the connecting link enabling them to maintain their common identity and life, there were (and still are) elements, which impede their socio-economic development and keep them in spiritual darkness." [14]The following statement by the U.S. State Department gives further insight into this darkness:

"Ethnic groups in all regions participate in the indigenous religious practices of secret societies, such as the Poro (for men) and Sande (for women). Secret societies teach traditional customs and skills to initiate youth into adulthood. In some cases Sande societies practice female genital mutilation." [15] *

*According to the World Health Organization, 66% of Liberian women aged 15-49 have been subjected to female genital mutilation. [16]

Other dark practices also continue to plague Liberian society, including voodoo and ritual killing. [17] The secret Leopard society, now outlawed, was one of the most notorious for its involvement in such activities.

Origin Myths: The Mano People [18]

“As to their

origin, the Mano “standard” version runs as follows: The first Mano was a man

named Zo Massakollo and he descended from the sky on a chain to a place called

Misalu. This town was located in Mandingo territory but inhabited by Mano, it

was later taken over by the Mandingo. Zo Massakollo became very rich and had a

large family. When he died, his children started to quarrel over their father’s

property. Because of this quarrelling, Gao, one of Zo Massakollo’s sons, left

Misalu and went south and he finally settled in the Wi area near the present

Sakleipie. He married there and had two sons, Zo Mia and Zo Fie.

“His sons were great hunters who, after the death of their

father, set out on a hunting expedition. During this hunt they lost their way

and finally got to Baytonwee, a town in what is now the Yamein clan.

“They settled

there, married and had many children. Zo Mia’s sons later found a number of

towns in Guinea and the sons of Zo Fie built some of the towns now belonging to

the Yamein clan. According to a number of genealogies collected in the clan, Zo

Mia and Zo Fie lived nine generations ago.”

Creation Myth of the Mano People: [19]

Wala created man, and appointed one of them to be the big

man or chief. Some time later, the big man complained that the others wouldn’t

listen to him, and asked Wala to give him someone to help. In response, Wala

created a woman out of seedlings. The big man immediately sent the woman for

water, but she refused. Again, the big man complained to Wala, but Wala told

him to go back to the woman, as she was the only one who was going to listen to

him.

Wala tried to have the water, the wind and the fire to take

care of and rule the people, but each time they complained out of fear of what

these forces could do to them.

Wala sent the big man and his woman to Wala’s farm, where

they were instructed not to eat any of the crops. Instead, dog was there to

take care of them and catch animals for them to eat. However, the big man and

his woman would cook the meat along with some of the crops growing on the farm,

so dog reported this to Wala. At first, Wala just sent the dog back to take

care of them. Then the couple had children and grandchildren. When Wala came to

visit them and saw that they had eaten the crops he had said not to, he told

them they would now become mortals. Then the big man and his woman killed the

dog out of revenge for telling Wala what they had done.

In other versions of the Mano creation story, the tribes

come from Wala marrying a woman or from Wala creating a man and a woman sent

down to earth, and their descendants became the various tribes. In areas

touched by outside influences, the creation myth follows more of the Biblical

narrative, where Wala first created animals, plants and finally humans made of

clay: “…Some of the clay-figures Wala burned in the fire and they became the

black people and those which he did not burn became the white people.” [20]

Liberia is a land of diversity and mystery. Though many aspects of the tribal histories and religious beliefs may remain that way, the future lies open ahead of them, to see what they will make of it.

[1] Dr. Fred P.M. Van der Kraaij, "The Grain Coast, Malaguetta Coast or Pepper Coast before 1822," Liberia Past and Present, accessed July 19, 2016,

[2] “Country: Liberia,” Joshua Project, accessed July 19, 2016, https://joshuaproject.net/countries/LI.

[2] “Country: Liberia,” Joshua Project, accessed July 19, 2016, https://joshuaproject.net/countries/LI.

[3]

“Liberia,” Wikipedia, last modified July 21, 2016, accessed July 21, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberia#Ethnic_groups.

[4] "International Religious Freedom Report: Liberia," U.S. State Department, November 17, 2010, accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2010/148698.htm.

[5] “History

of Liberia,” Vision Liberia 2027, accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.liberia2027.com/627324.

[6] “Country:

Liberia,” Joshua Project, accessed July 19, 2016, https://joshuaproject.net/countries/LI.

http://www.liberiapastandpresent.org/Peppercoastbefore1822.htm.

[7] "Kpelle - Religion and Expressive Culture," World Culture Encyclopedia, accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.everyculture.com/Africa-Middle-East/Kpelle-Religion-and-Expressive-Culture.html#ixzz4EtKxs9sL.

[8] "Dan, Da in Liberia," Joshua Project, accessed July 19, 2016, https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/11485/LI.

[9] Dr. Fred P.M. Van der Kraaij, "The Grain Coast, Malaguetta Coast or Pepper Coast before 1822," Liberia Past and Present, accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.liberiapastandpresent.org/Peppercoastbefore1822.htm.

[10] "Kissi Tribe: Tribal People of Africa," Gateway Africa, accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.gateway-africa.com/tribe/Kissi_tribe.html.

[11] “Mano, Mah in Liberia,” Joshua Project, accessed July

19, 2016, https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/16121/LI.

[12]Dr. Fred P.M. Van der Kraaij, “The Grain Coast,

Malaguetta Coast or Pepper Coast before 1822,” Liberia Past and Present,

accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.liberiapastandpresent.org/Peppercoastbefore1822.htm.

[13]

John R. Hinnells, ed., “Mende Religion,” A

New Dictionary of Religions, Blackwell Reference Online, 1995, accessed

July 19, 2016, http://www.blackwellreference.com/public/tocnode?id=g9780631181392_chunk_g978063118139214_ss1-75.

[14]

“History of Liberia,” Vision Liberia 2027, accessed July 19, 2016,

http://www.liberia2027.com/627324.

[15] "International Religious Freedom Report: Liberia," U.S. State Department, November 17, 2010, accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2010/148698.htm.

[16] “Female genital mutilation (FGM),” World Health

Organization, accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/prevalence/en/.

[17]

Dr. Fred P.M. Van der Kraaij, “Ritual Killings

Past and Present,” Liberia Past and Present, accessed July 19, 2016, http://www.liberiapastandpresent.org/RitualKillingsIndex.htm.

[18]

Kjell Zetterstrom, "Some Notes on Mano Beliefs," Paideuma 18 (1972): 172-73, accessed July 20, 2016, http:///www.jstor.org/stable/40341526.

[19]

Ibid., 173-74.

[20]

Ibid., 175.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.