|

| "Before European colonization. 7th to 16th century," My Continent Africa, accessed August 18, 2016, http://mycontinent.co/AfricaBorders.php. |

|

| "European territorial claims on the African continent in 1914," My Continent Africa, accessed August 18, 2016, http://mycontinent.co/AfricaBorders.php. |

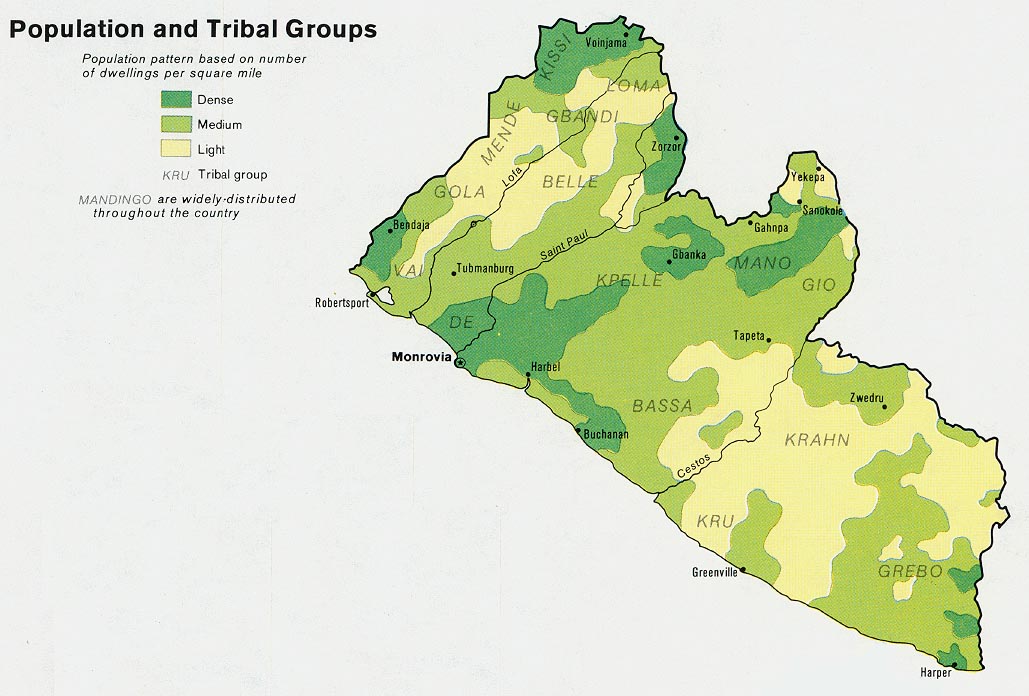

The fact that Liberia's borders have remained relatively stable does not mean, however, that they are organic in relation to the ethnic groups that make this territory their home. As the following map shows, Liberia's international borders cut through the tribal territories of the Vai, the Kissi, the Dan (or Gio), the Mano, the Loma, and more.

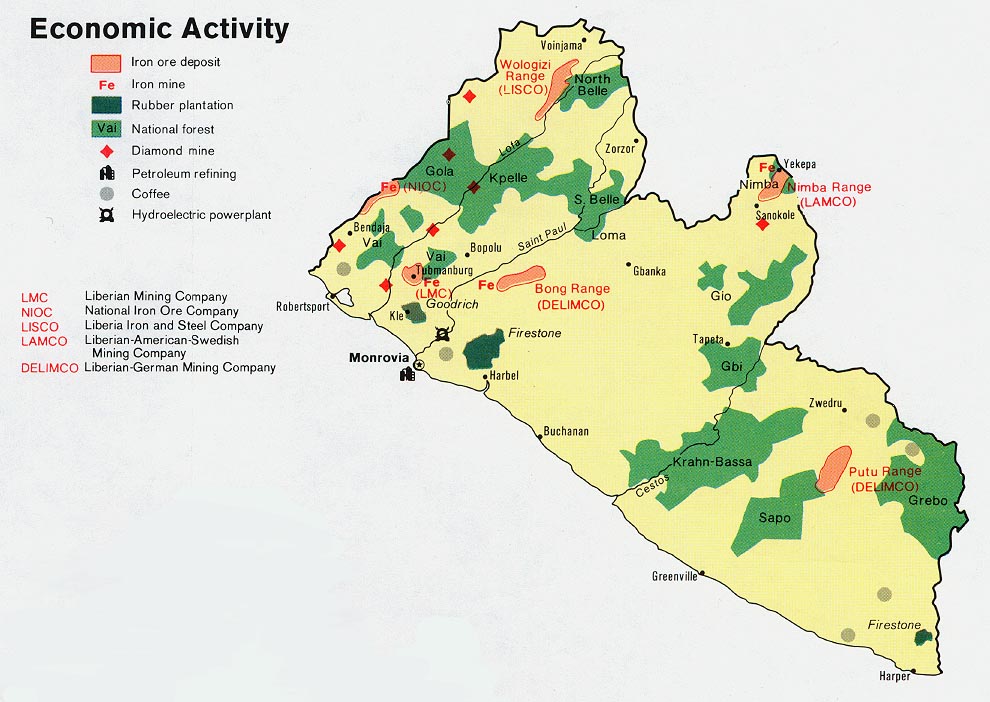

Having international borders that bisect ethnic groups has played a large part in the economic chaos that has plagued Liberia and other countries in the region. Whereas national economic recovery is largely dependent on accurate reporting and taxation, especially in such lucrative goods as diamonds, gold, and timber, the black market trading across unsecured borders detracts a huge amount of revenue for the country every year. While it is simply human nature to want to better your own financial standing and that of your relatives and tribesmen, this practice is extremely detrimental to the progress of the country of Liberia as a whole.

During the recent ebola outbreak, the issue of borders became a very hotly debated topic, as every effort was being made to contain the spread of the disease. As is described in the video below, there are dozens and dozens of unofficial border crossings, as people have family members who live on both sides of the border. Trying to close these borders in the event of a health crisis such as ebola proved both ineffective and next to impossible.

Video courtesy Benno Muchler, "At Porous Liberia Border, Vigilant People Prevent Spread of Ebola," VOA, April 7, 2015, accessed August 18, 2016, http://www.voanews.com/a/at-porous-border-vigilant-people-prevent-ebola-spreading/2709404.html.

[1] "Liberia: History," Encyclopedia.com, accessed August 18, 2016, http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Liberia.aspx.

Having international borders that bisect ethnic groups has played a large part in the economic chaos that has plagued Liberia and other countries in the region. Whereas national economic recovery is largely dependent on accurate reporting and taxation, especially in such lucrative goods as diamonds, gold, and timber, the black market trading across unsecured borders detracts a huge amount of revenue for the country every year. While it is simply human nature to want to better your own financial standing and that of your relatives and tribesmen, this practice is extremely detrimental to the progress of the country of Liberia as a whole.

During the recent ebola outbreak, the issue of borders became a very hotly debated topic, as every effort was being made to contain the spread of the disease. As is described in the video below, there are dozens and dozens of unofficial border crossings, as people have family members who live on both sides of the border. Trying to close these borders in the event of a health crisis such as ebola proved both ineffective and next to impossible.

Video courtesy Benno Muchler, "At Porous Liberia Border, Vigilant People Prevent Spread of Ebola," VOA, April 7, 2015, accessed August 18, 2016, http://www.voanews.com/a/at-porous-border-vigilant-people-prevent-ebola-spreading/2709404.html.

[1] "Liberia: History," Encyclopedia.com, accessed August 18, 2016, http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Liberia.aspx.